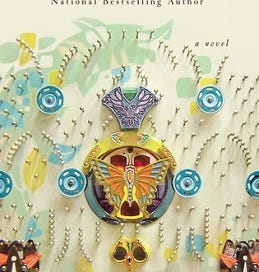

Quick Review: Pachinko

Pachinko, by South-Korean born and American-raised author Min Jin Lee, is the latest multigenerational saga to have entered the literary canon. It opens in 1910 in a small fishing village off the Korean coast, as a struggling family consider themselves blessed to find a wife for their only surviving son. Through the next three generations of the family, stretching across eight decades, the men mostly die young and the women mostly live long lives with more than their fair shares of suffering. Especially after moving to Japan in the 1930s they are never quite socially acceptable, despite accumulating substantial wealth through ownership of gambling parlours. (Pachinko, the game from which the novel takes its name, is similar to pinball, and fulfils much the same role in Japanese society as slot machines in the Anglosphere.)

My views from reading the book are similar to those of most people who have read it: it’s excellently written, fully deserves its status, but also could stand to be quite a bit tighter towards the end. Whole chapters are given to the perspectives of minor characters who fail to advance the main plot, or even to shed any light on the main characters.

Another criticism I have of the book is that, for all the attention given to the question of whether children can bear the stains of their ancestors’ deeds, we never really see any serious defence of the idea that they can. We see very clearly the pain and suffering caused by this belief; we see multiple characters who very clearly endorse that belief, in one case to the extent of committing suicide. Yet no character ever expresses the thought that such-and-such a person ought not to be trusted because of their parents’ deeds. It’s never humanised.

The moral status of the characters is intentionally left quite murky throughout the novel. The one unquestionably good character, Isaak Baek, dies a martyr in the early 1940s. Most of the other characters, with exceptions, are broadly well-meaning and hard-working people who are trying to live in a hostile world and to stay out of too much trouble. But at the same time, it’s made quite clear that their money is dirty. On the one occasion that a pachinko parlour owner’s friend attempts to become a customer, the owner immediately shuffles him out and refuses to let him ruin his finances over some ball bearings. The deeds of the most obviously evil character, Koh Hansu, are always kept quite firmly in the background or at least given a veil of plausible deniability – up until the point where he savagely beats a prostitute half to death. When I read the scene I was shocked at how it seemed to come from nowhere, but if you’re really paying attention to the kind of man that Hansu is it really shouldn’t.

The literary style of the book really creeps up on you: from reading the first 80% of the novel I would have struggled to say anything about the way it was written beyond the fact that it succeeded in consistently holding attention, then suddenly an American character was introduced and you immediately realise how much the narration changes. It’s a genuine achievement in easing you into a quite different way of speaking without any feeling of artificiality.

Overall I clearly have to recommend the book, but I also very much hope that Min Jin Lee will find the time to produce a revised edition cutting out some of the extraneous chapters.